NEWBURYPORT — John C. H. Young owned a barbershop on Merrimac Street at Green Street until he died in 1889 at the age of 72. His tombstone in the Old Hill Burying Ground says he possessed many virtues and was the poor of the poorest.

“He fed the hungry, clothed the naked, and was a father to the fatherless,” reads his epitaph. “Kind and obliging to all, he has finished his course and has gone to rest.”

The gravestone for Young, one of about 100 African American residents of Newburyport in the late 19th century, faces Auburn Street near Low Street, where from the early days of the port city stood Guinea Village, a neighborhood of black and a few poor Irish residents.

The southern section of what today is Pond Street was called Guinea Lane, and the hill on Hillside Avenue was known as Guinea Hill.

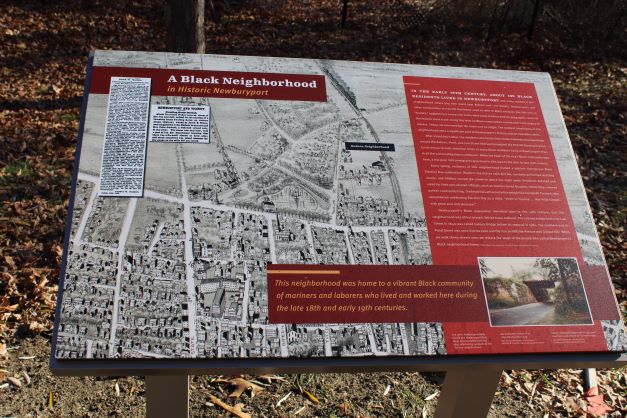

A newly installed sign on the Clipper City Rail Trail, just south of the Low Street bridge near the now-demolished Guinea railroad bridge, identifies the site of Guinea Village and honors the black residents who lived there as they helped build the city.

The narrative on the sign, entitled “A Black Neighborhood in Historic Newburyport,” was written by Dr. Kabria Baumgartner, a professor at Northeastern University; Cyd Raschke and Geordie Vining, as part of the Newburyport Black History Initiative.

One of 10 interpretative signs being erected in the city, the Guinea Village sign will be officially unveiled at 4 p.m. on Feb. 1. It and other signs, funded by the Community Preservation Committee and the City Council, are designed to educate and honor individuals and sites that played important roles in the city’s history.

“The Initiative is working to illuminate some of the community’s history that has been largely overlooked or forgotten, and is installing interpretive signs in the everyday public landscape of Newburyport’s core,” the Initiative stated.

Several of the signs will focus on stories of Black Americans who lived and worked in Newburyport from the pre-Revolutionary War era to the early 20th century.

“There is a lot more to Black history in Newburyport than slavery, and William Lloyd Garrison, and the underground railroad,” wrote Vining, the senior project manager for the city, who spearheaded building the city’s popular rail trails. “History can get buried fast, particularly about ordinary people. But some of the stories remain and have survived at the edge of our vision.

“In this first sign, and in others that will profile people who came before us, we are trying to uncover some of these stories for all to see.”

Vining wrote that there are big stories inside the smaller stories of individual lives.

Ghlee Woodworth, a local historian, wrote in her Volume II of Newburyport History that there were 30 black men and 29 black women living in the city in the 1780s. By the early 1800s, when the total population had grown to 10,000 residents, 100 were African American.

According to the Initiative’s interpretative sign, there were four times as many African Americans living in Newburyport than in the surrounding communities combined.

“The resilient inhabitants of this neighborhood were a significant part of Newburyport’s history and we remember them,” the sign on the rail trail states.

In Woodworth’s new book, she writes that the census recorded a gradual decline in the number of black residents. By 1900, when the total city population hit 14,000, the number of black residents had dropped to 50.

Life in Guinea Village sounds like it had its fun moments. The interpretative sign states: “Every spring, residents of the neighborhood hosted a jubilant home-grown Black Election Day celebration.” After listening to the candidates for office debate, “Revelers feasted on cake and ale, acrobats performed dazzling stunts and fiddlers roused the crowd to dance the night away.”

White resident George W. Parsons wrote in an article, entitled “Down in Guinea,” that the festivities went on with “great zest and pleasure.”

“The little neighborhood of Guinea gradually disappeared,” Woodworth wrote. “The elders passed on. Sons and daughters moved to other communities to be closer to relatives, job and marriage opportunities. But during the 20th century, Black families no longer chose to live in a separate neighborhood and settled in homes throughout Newburyport.”

Vining wrote that “Nearly everyone who has heard about this story recently has been fascinated to learn about this neighborhood.”

The city takes pride in its history, particularly in its older buildings, Vining wrote. “Most of the sites and buildings associated with the historical experience of Black people in Newburyport, however, have not been preserved.”

Young’s barbershop appears to be the Green Street parking lot.

Hoping to mainstream the memories of black Newburyport residents, Vining wrote: “These historic interpretive signs – placed in the everyday shared public landscape of our downtown – can play a role in building a more welcoming and inclusive community today and in the future.”

After dedicating the new Guinea Village sign on Feb. 1, the initiative will conduct a walking tour of the neighborhood, passing along the Rail Trail and over to Auburn Street. It will trace the footsteps of the past inhabitants of this neighborhood and end at Young’s grave. Parking for the event is being provided at the Graf Skating Rink.

The Guinea Village sign on the Clipper City Rail Trail