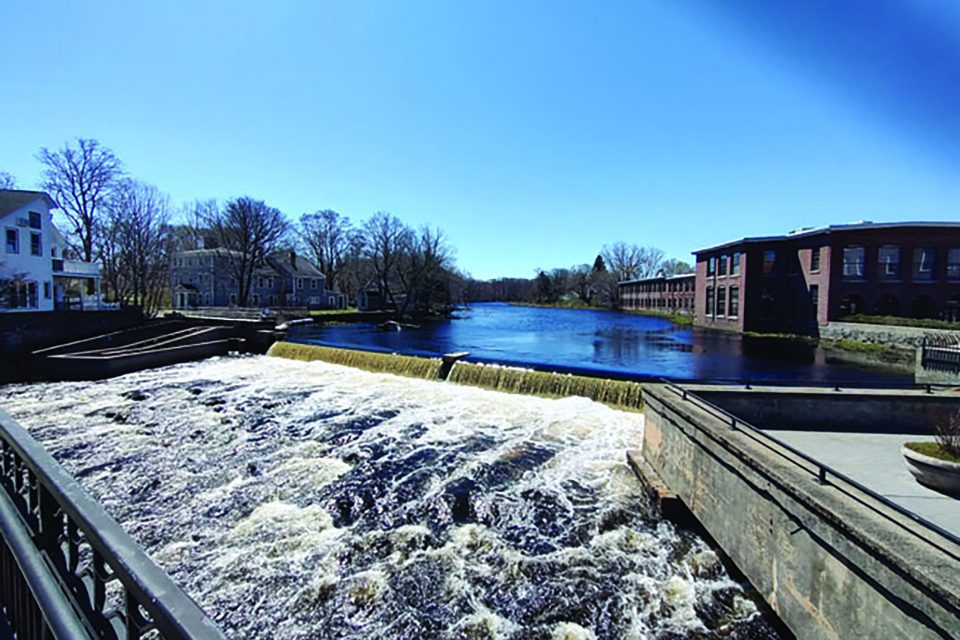

IPSWICH — To listen to Neil Shea of the Ipswich River Watershed Assn., a lot of shad, herring and baby fish are looking forward to the town removing the Ipswich Mills Dam from the river in downtown.

The dam, built in 1908 to produce power for the mills along the river, has blocked the fish from swimming upriver to lay their eggs for more than a century.

After debating the removal of the dam for a decade, the SelectBoard last week voted four to one in favor of removing the town-owned dam adjacent to the EBSCO building.

The vote follows the Town Meeting decision last year where 68 percent of the those attending voted to pursue permits to remove the dam. This year, 58 percent of voters supported the dam removal in a non-binding ballot vote last month.

In front of a packed meeting room crowd in town hall, SelectBoard member Carl Nylen made the motion and fellow member Sarah Player seconded it to have the town move forward with the dam removal. They were joined by Charles Surpitski and Michael Doughtery, while chair Linda Alexson voted against removal.

Alexson, who said her priority was protecting the $100 million, Ipswich shellfish industry, which uses the downriver shellfish beds, wanted to have the sediment that is backed up in the riverbed tested for contaminants before the town voted to have the dam removed.

“It is not a risk I’m willing to take,” the chair said, noting that the Ipswich shellfish set the town apart from the rest of the state. “I am opposed to taking any risk to those shellfish beds.”

Alexson reminded the board that the shellfish beds were closed for decades because of “horrible pollution” that came from the rows of mills along the river that were powered by the dam.

The Ipswich Mills Dam, which does not seem to serve much of a purpose since it was decommissioned in 1932, is the most impactful dam on the Ipswich River. It is the first dam upriver from the sea that migratory fish encounter.

At the ‘head-of-tide’, it represents a hard stop between fresh river water and the saltwater estuary at the river’s mouth. A fish ladder was installed in 1995 to help fish migrate upriver.

But according to the watershed association, “even the best fish ladders pose issues for migratory fish.”

Shea, the watershed’s restoration manager, said the current fish count, which is done manually and by video, shows a growing number of fish waiting downriver from the dam.

“The fish are waiting to get upriver to lay their eggs,” he said. “There are more fish waiting to get up the fish ladder than can get up it.”

That is the reason the removal of the Ipswich Mills Dam has gotten so much attention nationally, Shea said.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (F&WS) had agreed to donate $1.2 million as part of what was described as a “good amount of funding” for the dam removal. The National Ocean Industries Assn. has donated $120,000, about half of which has been spent in preparing the dam to be removed.

The state and federal agencies have also indicated an interest in funding the dam removal, Shea said. “We are fortunate that there is a significant amount of funds available right now.”

Neal Price with the Horsley Witten Group, a consultant on the dam removal, outlined a detailed plan for multiple sediment sampling and testing that will be sent to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) before dam removal can proceed.

If any sediment samples are found to be contaminated above the department’s threshold for toxicity, it would “trigger further investigation and mitigation,” Price told the SelectBoard.

When the dam is removed, natural river processes will return and the tide will extend another 1.5 to 2 miles upriver, creating a freshwater tidal habitat, which the watershed association called “the rarest aquatic habitat in Massachusetts.”