NEWBURYPORT – It may surprise you that this city, which erected a statue in front of City Hall to slavery abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, once refused to let black children attend its public schools.

In the early 1800s, long before the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th Century, African American girls applied to attend the public schools and end generations of denying education to black children.

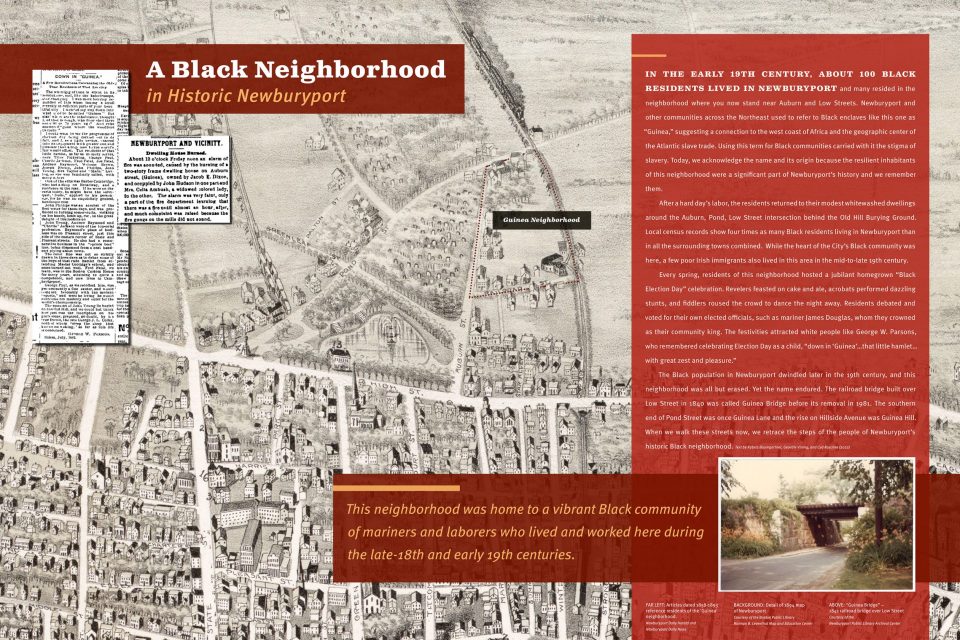

In 1820, the girls from the mostly black neighborhood off Low Street, called “the Guinea,” presented themselves at the grammar schools, asking to attend classes like the white students. The School Committee said no.

It took another generation, until the 1840s, for black students to be allowed to attend Newburyport schools.

The city is preparing to erect a sign in a prominent place that tells that story for residents and visitors. It will be one of 10 interpretive signs placed on the rail trail, in parks and downtown. The city is installing the signs to “Illuminate some of Newburyport’s history that has been overlooked or forgotten by many,” Geordie Vining, senior planner in the city’s Planning Department said last week as he asked permission for the signage from the Parks Commission.

With the Parks Commission’s unanimous approval and a $53,000 grant from the Community Preservation funds, the city will erect the signs to “Explore and amplify previously unacknowledged voices from the past, consider historical themes and storylines from new perspectives and enhance and inform Newburyport’s collective understanding of its past and contribute to a more inclusive history of our community,” according to Vining’s presentation.

A sign recognizing the Guinea neighborhood will be erected at the Low Street bridge on the Clipper City Rail Trail in the Auburn, Pond, Low Street area.

Another sign recognizing the black anti-slavery activists in Newburyport is planned for Brown Square near Garrison’s statue. There will also be signage at Tracy Square, Inn Street and in other downtown sites and at the Market Landing Park.

The city is working to uncover its black history with Dr. Kabria Baumgartner, an associate professor of History and Africana Studies and associate director of public history at Northeastern University, and Dr. Cyd Raschke, board member of the Coastal Trails Coalition, the Newburyport Education Foundation and past president of the YWCA.

Also contributing information on the city’s black history are the Museum of Old Newbury, the archival center of the public library, the historical commission, the Newburyport Preservation Trust and the Custom House Maritime Museum, plus independent historians and authors Marge Motes, Skip Motes and Ghlee Woodworth.

Many sites associated with historical experience of black people in Newburyport have not been preserved due to redevelopment, fire, highway construction and urban renewal clearance, Vining’s presentation states.

In the 1820 census, Newburyport recorded 6,852 people with almost 100 black residents, including 40 children. There were 10 black residents in Newbury, 15 in Salisbury and two in West Newbury.

Long before there were annual celebrations like Yankee Homecoming and waterfront concerts, the black community here held a yearly Election Day street party on what was then called the Guinea Bridge.

Black activists used petitions and lawsuits to fight for freedom for slaves. In 1773, a Newburyport slave, Caesar Hendricks, sued his owner for “detaining him in slavery” and won damages imposed by an all-white jury.

Newburyport’s Caesar Sarter published an influential essay in 1774 in the Essex Journal and Merrimack Packet. Nancy Gardner Prince, born in Newburyport in 1799, became an abolitionist who gave public lectures in front of mixed audiences of men and women, a radical practice at the time.

Vining said there will be an interpretative sign near the waterfront to honor black mariners, who made up about one in five Newburyport sailors. Profiles of black sailors will include Daniel Cottle, who sailed on the privateer Dalton and died in 1777 of smallpox in a British prison while nursing other sick prisoners.

There will also be a profile of 19-year-old James Hall, who was kidnapped in 1815 and forced on to the Wallace, a Newburyport ship, in a reverse underground railroad seizure. Also profiled will be Evans Covington, a Newburyport barber, who enlisted in the Navy from 1860 to 1863 and then enlisted in the Massachusetts 54th Army Regiment. Evans died in insane asylum in 1864, but his wife Victoria was denied widow’s pension by federal government.

Dozens of black men from Newburyport served as soldiers in the Revolutionary and Civil wars. Among them was Pomp Jackson, a soldier and fifer in the Continental Army from 1776 to 1783. He bought his emancipation with five shillings.

Black-owned businesses in 19th century could be found on Elbow Lane as well as on Liberty, Water and Merrimac streets. They included several barbers like John C. H. Young, who is buried in Old Hill Burying Ground.

Peter Romily was a restauranteur in the 1860s and 1870s. His daughter, Isabella, was educated at Perkins School for Blind and taught music in the 1890s.

Louis Clarkson Tyree, who lived from 1884 to 1963, boarded and worked at the Wolfe Tavern in the early 20th century while he attended Newburyport High School and Phillips Exeter Academy. He graduated from college and law school and was helped by the Newburyport Harvard Club in 1912 with a $150 scholarship that paid 60 percent of his annual Harvard Law School tuition.

One of the more colorful figures was Moses Prophet Townes, who lived until 1951. He moved from Virginia to Newburyport and worked for more than 50 years at the historic Wolfe Tavern and the Garrison Inn as a doorman and porter. Described as “suave and popular,” Townes brought his siblings to Newburyport. He was caught in a prohibition sting in 1929, offering liquor at the tavern. It cost him a fine of $100, two months salary. He lived with his wife Eliza on Titcomb Street.

Vining said the black history signage will “enhance the essential character of the city, enhance Newburyport’s National Historic Register District and serve a significant number of residents” who have not been given the recognition they deserve in this historic city.