NEWBURYPORT – During World War II, the father and three uncles of the future Essex County sheriff Frank Cousins, Jr. enlisted in the Navy, Merchant Marine and Army Air Forces to fight against Germany.

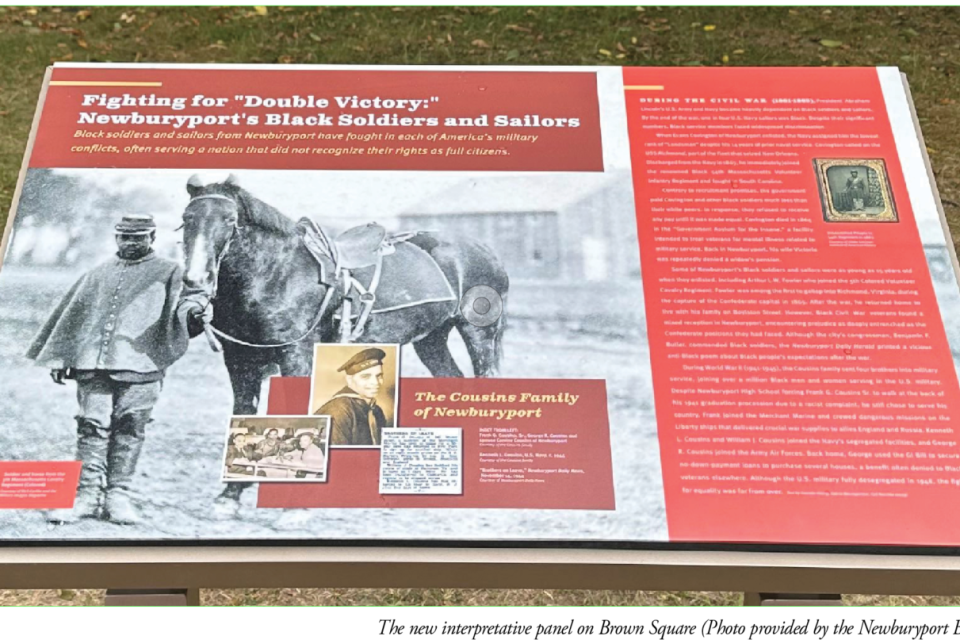

A new interpretative panel, “Fighting for Double Victory, Newburyport’s Black Soldiers and Sailors,” on Brown Square near Green Street in front of City Hall recognizes the service of African American soldiers and sailors from Newburyport, including the four Cousins brothers.

It will be officially unveiled at 3 p.m. Dec. 5 during the week the community honors the liberator William Lloyd Garrison, who fought for an end to slavery in the 19th Century.

Frank Cousins Jr. and William (Billy) Cousins will speak at the unveiling.

“My family is very happy” with this recognition, Frank Cousins Jr. said last week. “This is a nice thing for Newburyport. It is a very nice thing for my family.”

“Frank (Cousins Sr.) joined the Merchant Marine and crewed dangerous missions on the Liberty ships that delivered crucial war supplies to allies England and Russia. Kenneth L. Cousins and William J. Cousins joined the Navy’s segregated facilities, and George R. Cousins joined the Army Air Forces,” the new panel states.

Written by three founders of the Newburyport Black Initiative, Geordie Vining, Kabria Baumgartner and Cyd Raschke, the panel along with a dozen others around the city is designed to inform current and future generations about the roles African-American residents of Newburyport played in its history.

Other panels have focused on a black neighborhood, called the Guinea, on black businessmen, sailors and civil rights activists. The initiative also identified and honored black residents who were buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery without headstones.

Vining is the senior project planner for the city of Newburyport. Baumgartner is a professor at Boston University. And Raschke is an author and community leader.

After serving in the world war, the Cousins brothers returned home to be prominent members of the Newburyport community. George Cousins used the GI Bill to secure no-down-payment loans to purchase several houses, a benefit often denied to Black veterans elsewhere.

Before joining the Merchant Marine to fight the Nazis, Frank Cousins Jr. attended Newburyport High School. On graduation day, the school principal insisted that he walk at the back of his 1941 graduation procession because another student objected to walking beside a black student.

His son, one of eight children, served on the Newburyport City Council, in the state legislature, as sheriff and as a president of the Greater Newburyport Chamber of Commerce. He continues to serve his community on the board of Whittier Technical School.

The U.S. military was fully desegregated in 1948, although the fight for equality in the ranks continued.

Black residents of Newburyport also fought in the U.S. Army during the Civil War.

“President Abraham Lincoln’s U.S. Army and Navy became heavily dependent on Black soldiers and sailors,” the new panel states. “By the end of the war, one in four U.S. Navy sailors was Black. Despite their significant numbers, Black service members faced widespread discrimination.”

Evans Covington of Newburyport, who had 14 years of naval service enlisted in the Navy, but was given the lowest rank of “Landsman.” Covington sailed on the USS Richmond, part of the fleet that seized the city of New Orleans, the panel states.

“Discharged from the Navy in 1863, he immediately joined the renowned Black 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment and fought in South Carolina. Contrary to recruitment promises, the government paid Covington and other Black soldiers much less than their white peers. In response, they refused to receive any pay until it was made equal,” the panel states.

Covington died in 1864 in the “Government Asylum for the Insane,” a facility intended to treat veterans for mental illness related to military service. At home in Newburyport, his wife Victoria was repeatedly denied a widow’s pension.

Some of Newburyport’s Black soldiers and sailors were as young as 15 years old when they enlisted. One was Arthur L.W. Fowler, who joined the 5th Colored Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. Fowler was among the first to gallop into Richmond, VA, during the capture of the Confederate capital in 1865.

After the war, he returned home to live with his family on Boylston Street.

“Black Civil War veterans found a mixed reception in Newburyport, encountering prejudice as deeply entrenched as the Confederate positions they had faced. Although the city’s congressman, Benjamin F. Butler, commended Black soldiers, the Newburyport Daily Herald printed a vicious anti-Black poem about Black people’s expectations after the war,” the panel states.

♦