PLUM ISLAND — This story of this beautiful barrier island is that of two islands.

To the north, sandwiched between the Great Marsh, the Merrimack River and the Atlantic Ocean, people reign, building ever larger and more expensive homes that battle erosion from rising seas.

To the south, birds dominate in a federally protected refuge that was built as a compromise between hunters and conservationists.

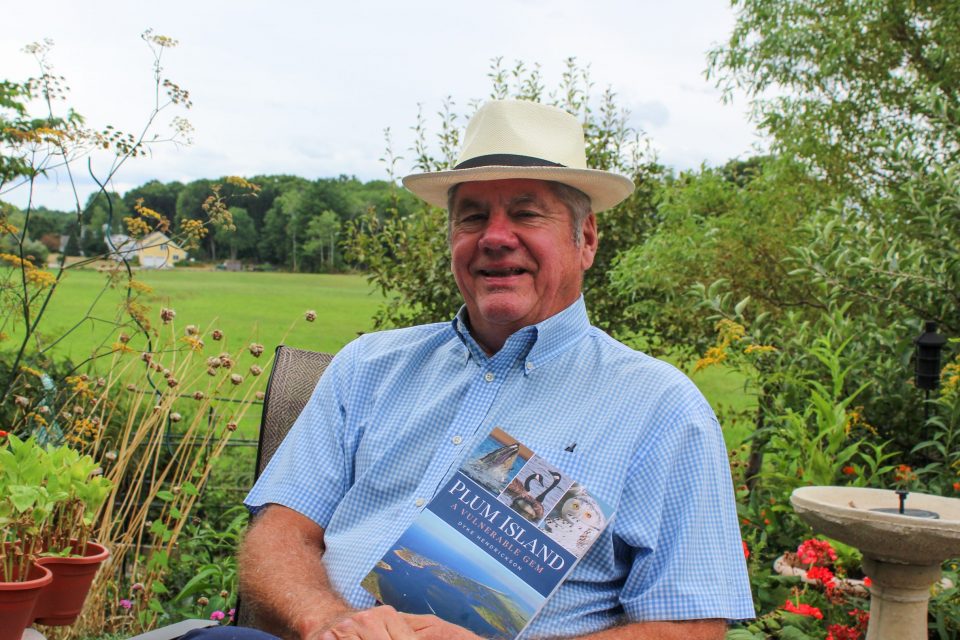

It makes for a colorful history and controversial future for this 11-mile-long island, which Newburyport historian and author Dyke Hendrickson calls A Vulnerable Gem in his latest book.

The 120-page book with 75 exceptional photos of historic sites and birds in flight explores the forces – human, wildlife and nature – that define Plum Island’s history, current status and its future. Hendrickson’s book can be purchased at Jabberwocky BookStore.

“Plum Island is so beautiful,” Hendrickson said in an interview last week. “The views are spectacular.”

Asked why he wanted to write about Plum Island for his seventh book, he said it was the birds that captivated his imagination. “I wanted to write about the contradictions and the glory of the whole place.”

According to the book, the island was first included on European maps in the early 17th Century. The Vikings may have visited the island, and French explorer Samuel de Champlain sailed by it while surveying the Massachusetts shoreline. Captain John Smith, of Pocahontas fame, sailed north from Virginia and visited Plum Island in 1614. He wrote a detailed description, but did not name it.

It was almost named Isle Mason after a land grant to Captain John Mason that included the island. Ultimately the name Plumb Island stuck, after its large number of plum bushes, Hendrickson wrote.

Fishing and farming dominated the island for much of its early history. But it was the popularity of hunting black ducks beginning in the 1880s, which prompted the construction of several hotels, now gone, on the island.

It also caused the first major fight for control of the island. The battle over killing versus protecting birds became intense, according to Hendrickson, when Stoneham-resident Annie Brown donated $100,000, a lot of money in those days, in her will to bird clubs so they could buy land on Plum Island.

The resulting lobbying campaign by birders caused the federal government to dedicate 10,000 acres on the island for wildlife.

Hendrickson described in detail how the hunters fought back trying to reduce the amount of protected acreage, a political battle that went all the way to President Truman’s White House. The government reached a compromise in 1948, in which 4,700 acres were established as a permanent federally protected refuge. The Parker River Wildlife Refuge was created.

One of Hendrickson’s heroes was Rachel Carson, an environmentalist who studied the Plum Island black duck. She later wrote the book Silent Spring, which advocated for the duck’s preservation by having the government ban the pesticide DDT.

Because of Carson, “The birds were safe,” Hendrickson said.

Plum Island has always attracted daily beachgoers. They first came by horse-drawn busses and later a rail line from downtown Newburyport to the beach. The beach became a lively place, much like Salisbury Beach in its day, with a dance hall and concerts.

“It sounds like it was a lot of fun,” Dyke said.

The challenge for visitors today is where to park. A new battle has emerged between residents and beachgoers, who come looking for a place to leave their car, only to encounter “No Parking” signs up and down the streets.

For Plum Fest, shuttles take beachgoers from the airport to the beach.

Hendrickson said the islanders need to think through the parking issue because it is so annoying to non-islanders, who are taxpayers. The island residents need government revenues to fight erosion, he said.

The battle over erosion is well publicized, with Boston television news crews chronicling the demise of expensive homes built on the dunes. As sea rise occurs, erosion persists and homeowners try to counter by mining sand and bringing in boulders.

To make the mouth of the river, one of the most dangerous in the country, safer for boaters, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has lined it with boulders, a long-standing practice.

“In 1829, an attempt was made to increase the depth of water at the bar the mouth of the Merrimack by the construction of a breakwater extending from Plum Island to Woodbridge Island. The breakwater did not prove to be effective and eventually was destroyed by wave and water action,” Hendrickson wrote at the close of his first chapter.

And then there are the protected plovers. For several weeks each summer, the beach is off limits to beachgoers while the plovers breed. Hendrickson, as a local reporter, sat through numerous forums of angry residents who want to walk their dogs or drive off-road vehicles on Plum Island beaches. He suggested, mostly in jest, that the federal government should build the plovers their own “bordello.”

Among Hendrickson’s other books are Nautical Newburyport: A History of Captains, Clipper Ships and the Coast Guard; New England Coast Guard Stories; and Merrimack, the Resilient River.